Introduction

The global lockdown beginning in 2020 allowed some wildlife to venture into cities, like foxes, coyotes, and birds. The paper “What can we learn from wildlife sightings during the COVID-19 global shutdown?” by Zeller et al. (2020) in Ecosphere encompasses both an ecological and social study. The author uses citizen science data to explore changes in wildlife observations during the pandemic. This paper caught my attention due to the discussion in class about the pause in human activity during the pandemic and how urban wildlife behavior is intertwined with our presence.

Summary

Zellmer and colleagues analyzed citizen reported wildlife sightings from platforms like iNaturalist and eBird, comparing data from the early months of the pandemic to previous years. The purpose was to figure out whether wildlife actually became more abundant in cities during lockdown or if people only noticed a greater abundance of animals because they were at home and actually paying attention.

Results

They found mixed evidence. Reports increased of wildlife sightings in many urban areas, but this does not mean that there were necessarily more animals. Species that appeared more frequently in urban environments were coyotes, deer, and foxes. These were species that typically avoid dense human spaces. The paper emphasized that changes in behavior varied by species, city, and the degree of lockdown strictness. They ultimately, highlighted, that human movement can drastically alter the visibility and distribution of urban wildlife. A big portion of the paper is dedicated to acknowledging what the data cannot prove due to observer effort bias, detection vs. abundance, and heterogeneity among cities. The article never comes to an exact conclusion that wildlife increased in urban areas during lockdowns, but rather raises possibilities and promotes cautious interpretation.

Critical Reflection

This study is strong in that it used this rare global event as a large-scale natural experiment. The use of citizen science allowed for fast data collection and broad spatial coverage during a difficult time. The article is also rightfully cautious in not claiming “nature reclaimed cities” and instead acknowledging biases in observation and sampling. This underlines that this study is more of an analysis of human behavior rather than animal abundance. All in all this reflects on their credibility, making it a more reliable source. However, the authors could have gone further in correcting biases, rather than simply acknowledging it. For example they could have implemented observation models and categorization, which could have helped them separate real life wildlife increases from high detection rates. Furthermore, the study focuses on the early stages of lockdown in 2020, when in reality animals responses to the lockdown evolved over time. A study comparing all years of lockdown would test whether behavioral flexibility persists. Further studies could combine citizen science with automates monitoring, such as camera traps, sensors or tracking collars. Additionally, comparing results across continents could reveal cultural or infrastructural influences on how wildlife adapted depending on the density of buildings, size of city, noise pollution etc.

Work Cited

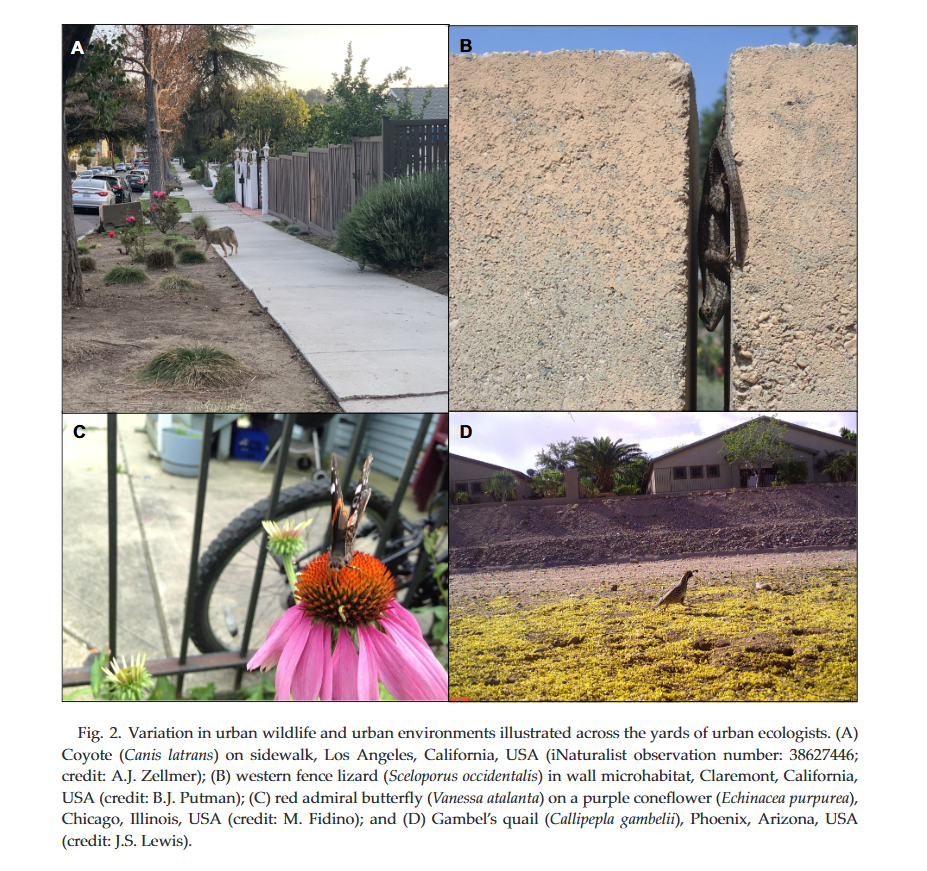

Zellmer, A. J., Wood, E. M., Surasinghe, T., Putman, B. J., Pauly, G. B., Magle, S. B., Lewis, J. S., Kay, C. A. M., & Fidino, M. (2020). What can we learn from wildlife sightings during the COVID-19 global shutdown? Ecosphere, 11(8), e03215. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3215