Introduction

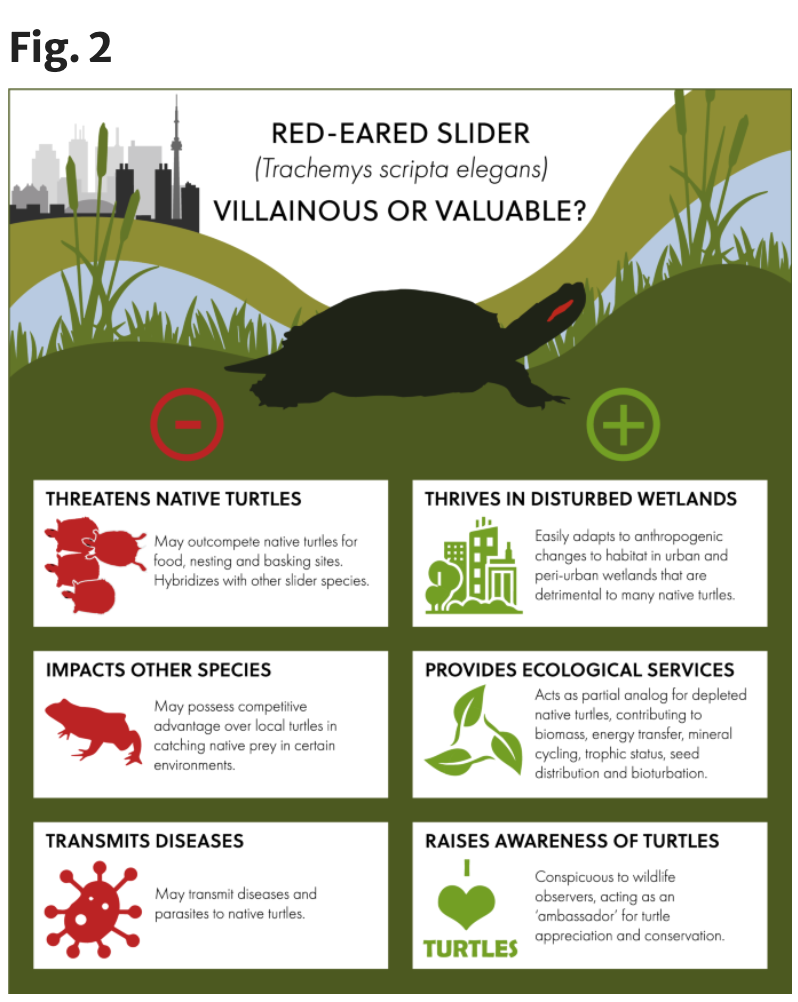

Population distribution and gene flow depends heavily on habitat connectivity. Fragmentation of natural areas causes genetic differentiation in urban landscapes. The consequences of fragmentation depends on the species; generalist species (wild boars) adapt better to artificialisation by exploiting resources available around smaller fragments. Wild boars prefer environments with dense vegetation, which provides them both shelter and food. The mobility and use of space of wild boars reflects their decisions balancing the benefits of exploiting a resource and the dangers it takes to reach them. Human disturbance here is the real danger. Human disturbance and habitat fragmentation leads to higher mobility and higher nocturnality. SDM (Species distribution models) are powerful tools to identify the distribution area of a species. These models generate statistical relationships between the probability of presence between species and environmental variables, such as land use, landscape metric, climate or topography. Using survey data this method can predict the ranges of species based on current or future environmental factors. This method was used in this study predict urban boar’s range and assess landscape features selected or avoided by this species. The first hypothesis being that wild boar’s presence in urban areas is determined by access of resources and modulated by avoiding densely built up areas. The second hypothesis is that Bordeaux’s urbanistic green frame is suitable for wild boars.

Methods

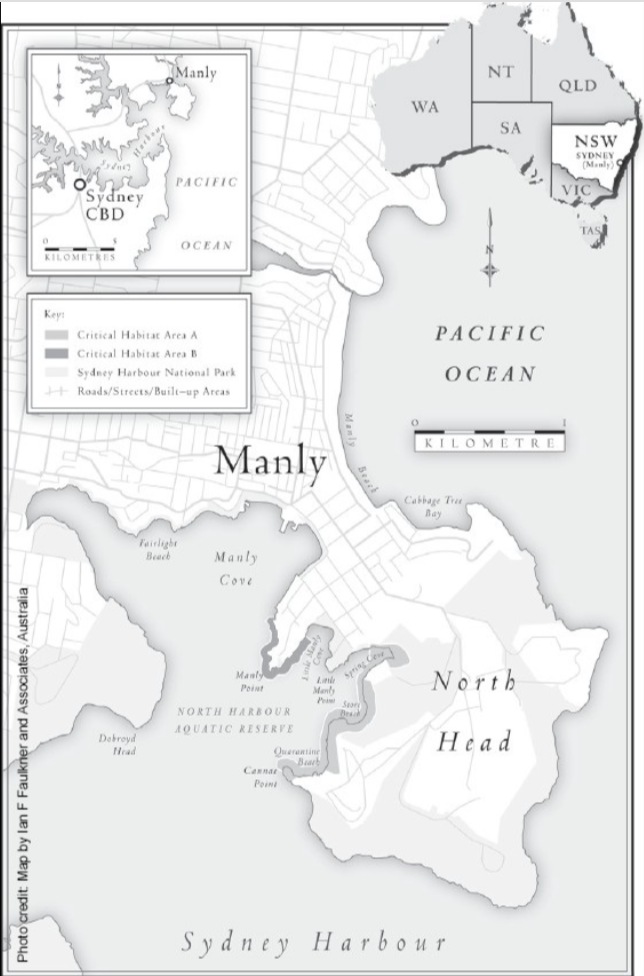

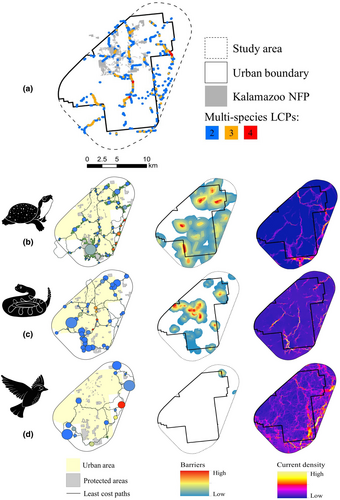

This study took place in Bordeaux Metropolis (southwest France). The study area was divided into 100-hectares cells, equaling 524 observation units. A third of these units (174) were randomly selected and explored from 25th March to 10th May 2019 to detect wild boar presence. Observations included sightings, rooting sites, wallows and trails. Other clues like footprints, rubs, hairs, or beds confirmed wild boar frequent the area. Cells where boars were present in were given an observation score of 1 (corresponding to a 100% probability that animals have been there) and the cell assigned 0 corresponded to absence of species. Then the probability of wild boar’s presence in each grid cell was studied using logistic regression models (R 4.03 software and QGIS) incorporating several predictor variables. These environmental variables included 1) physical obstacles to animal movements; 2) degree of human impact; 3) availability and accessibility of resources (food, water and shelter).The Garonne river and Bordeaux’s ring road were also seen as physical obstacles for the wild boar. Therefore, every grid cell was labeled based on its position to the river and its centrality to the road ring. The density of buildings was and roads was calculated in each grid cell and a French topographic database was implemented for metric precision. Hosting potential of a grid by a wild boar was estimated by calculating the surface area of lands that tend to provide resources and by assessing the level of fragmentation of forest habitats included in the cell. Overall by categorizing grid cells in three categories on level of amount refuge and food it was determined that 53.6% of the total study area had either refuge or food if not both. After removing correlated variables, they tested multiple model combinations and selected the best fit using AIC, BIC, and TSS metrics. The strongest model (TSS = 0.79) showed that wild boar presence increased with larger green areas (WBGF) and decreased with higher building density, confirming that access to resources and avoidance of dense urban zones best explained their distribution. Predicted probabilities were mapped to identify areas with high (>50%) or low (≤50%) likelihood of wild boar presence. Results showed that nearly 90% of the urban green frame was suitable for wild boars, especially outside the ring road and on the right bank of the Garonne River. A year-long camera trap survey beneath the ring road recorded 114 wild boars, confirming that animals use this underpass as a corridor between suburban and inner-city green spaces, validating the spatial model’s predictions about connectivity.

Results

Model analyses showed that wild boar presence in Bordeaux was mainly driven by the availability of green habitats and limited by building density. The best logistic model confirmed that wild boars were most likely to occur in areas with extensive wild boar green frame (WBGF) and fewer urban structures, especially outside the ring road and on the right bank of the Garonne River. Overall, 68.9% of grid cells had a predicted boar presence probability above 0.5, closely matching field data where presence was observed in 67.8% of surveyed cells. Nearly 90% of the green frame showed a high probability of use. Inside the ring road, boars were mostly present on the right bank (70.5% of green area likely occupied) but rare on the left bank (22%). Camera trap data supported these predictions, showing frequent use of an underpass beneath the ring road, with boars moving both into and out of the city. This confirmed that while boars prefer peripheral green zones, they can cross barriers and access central urban areas through existing corridors.

Critique

The study was successful in using statistical modeling intertwined with field observations to understand urban wildlife niches. The author’s use of statistical models like SDMs and QGIS and R provided a thorough, clear, and replicable method for assessing environmental variables. Overall the variety in methods like field observations, camera monitoring, and spatial analysis makes the research highly reliable. However, there were some limitations to the study. For one, the field survey took place over a short period of time during a single season (spring). This small temporal scope may not capture the variation in boar behavior across seasons. Additionally, using whole 100-hectare grid cells may miss fine-scale behavioral patterns and small habitat use within fragmented areas. Furthermore, the cells with no seen boar behaviour within were marked as “absent”. This is tricky, because assuming absence of evidence is one thing , but this does not give us the right to assume actual absence of the presence of boars in that grid. Lastly, it would’ve been beneficial to include social attitudes to implement in the coexistence between boars and humans. All in all, the paper provides valuable knowledge about how generalist species exploit urban environments and how we must acknowledge the coexistence of these species and us.