Urban trophic systems that involve mammals are a largely understudied field. Barriers to this research include the cost of conducting field observations or DNA analyses. Camera traps can be a cost-effective method to opportunistically record predator-prey interactions. Potential prey encounters can also be recorded with camera traps and used to build trophic networks.

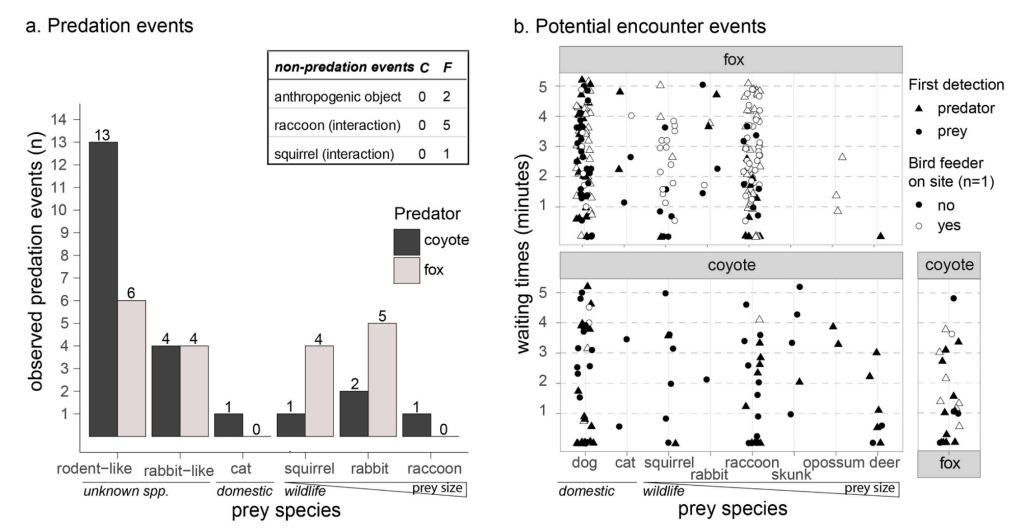

This study was conducted in Toronto, Canada, a highly urbanized area. The focal predator species were red foxes and coyotes because they have opportunistic diets and have adapted to thrive in urban areas. 33 motion-detecting cameras were placed at approximately knee height on trees and lamp posts along previously laid transects throughout the city from October 2020 to September 2021. Any image containing more than two animals was considered a predation event. Potential predation events were recorded as each species was detected on the same camera less than five minutes apart. This data was used to create bipartite networks that demonstrate the urban predator-prey interactions and potential interactions. Their results found a total of 43 combined predation events and 299 combined potential interactions for red foxes and coyotes.

Images of recorded predation events by coyotes (uppers) and red foxes (lower)

The first thing this paper failed to address was the impact of COVID-19 protocols in urban areas on these predator-prey interactions. I suspect that over the course of the study, restrictions lessened, which would likely be associated with a decline in these interactions in urban areas, as we have discussed in class. Regarding the researchers’ methods, site-specific information should’ve been included in their analysis of interactions to develop a more intricate food web of the whole study area. I also think it would be important to note whether the prey or predator was detected first when documenting potential predator-prey interactions. The difference could be significant enough to remove some of the observations as potential interactions. Also, the researchers of this paper urge future researchers to consider the likelihood of a predation event in their analysis of potential encounter events, which could also result in a more detailed food web.