Overview:

Chronic wasting disease has become an increasing concern for white-tailed deer in the U.S. Along with this, urban deer densities have risen as more areas are urbanized and deer populations grow. This leads to an aggregation of deer, as they have smaller spaces to occupy around human residential communities and gardens. CWD is transmitted at highest frequencies when there is high traffic of deer over one area. Storm Et. Al. researched the connection between deer density, landscape features, and soil clay content with chronic wasting disease transmission. The study was conducted on young white-tailed deer, less than 2 years old, in Wisconsin.

Methods:

They conducted this study in areas nearby reported CWD outbreaks. They collected samples from lymph nodes of harvested deer by hunters. Registration, including the location of deer harvested, was mandatory. Most deer were harvested in fall, giving them 1.5 years of potential exposure time. Helicopter counts were used to estimate deer density in research areas. Data from the National Land Cover Database and data from NRCS Survey Spatial and Tabular Data around the CWD core areas were used for landscape and clay soil content connections.

Results:

Their findings actually showed that traditional density models did not have a linear correlation with CWD cases. They did find a positive relationship between deciduous forest landcover and CWD cases.

Discussion:

They stated that the social dynamics of yearling deer are likely too complex for density relationships to predict CWD transmission. Social dynamics are matriarchical at young ages, and circles change throughout a deer’s life, meaning deer are interacting in large webs. However, deciduous forest cover was a reliable predictor, likely due to high use of these spaces by deer.

Critical Analysis:

They looked at a lot of factors that could contribute to CWD transmission, but did not focus in on one. I feel like there were a lot of lurking variables in this study, and there could be some answers missed. Mostly, I think it’s worth looking specifically at deer density by comparing a wildland area with an urban/suburban area. That might produce clearer results on the relationship between deer density and disease prevalence. However, I recognize that the limitation here is the culling of deer for sampling in urban/suburban spaces.

Author: Claire Elyse Rusconi-Warner

Black Bear foraging behavior in urban landscapes

Posted onBackground:

Black bears require a very high caloric intake leading up to the cold months when hibernate. They depend on a decent yield of soft and hard mast production in order to reach these nutritional needs, but sometimes hard or soft mast yields may drop too low to sustain Black bear populations. When this happens, bears need to forage for alternate food sources. Urbanization has been rapidly increasing which alters what these Black bear populations are exposed to. Being highly adaptive creatures, Black bears have come to use human garbage as an alternate food source. For urban bears, garbage can be easily accessed and can be high in calories.

This study was conducted in order to understand their foraging ecology in urban landscapes. The goal of the research is to find better solutions to mitigate human-wildlife conflict with Black bears.

Methods:

This study was conducted in the urban areas of Aspen, Colorado. During the months of May-August, researchers captured bears and fitted them with radio collars that were programed to report the bear’s locations every 30 minutes between May-September. From 2007-2010, researchers tracked 40 bears during May-September, which is their active season in Colorado. They backtracked to bear locations then inspected the area to see whether there is evidence of natural or anthropogenic foraging evidence. The area they would search at each back-tracked location had a 20 meter radius. They remotely downloaded data and backtracked to the most recent 24 hours of location data. They did not backtrack to the most recent location in order to avoid disturbing the bears, and they only used locations that were within 50 meters of a building.

Natural foraging evidence included animal carcasses, broken foliage, turned over rocks, ect. Anthropogenic foraging evidence included scattered garbage, visual observations of people present, broken limbs on landscape trees, broken windows, ect.

They used the backtracking data to summarize spatial and temporal patterns of the bears on natural and anthropogenic food sources.

Results:

Prehyperphagia refers to the months of May-July. Hyperphagia is when bears greatly increase their food intake prior to winter, during the months of August-September. Garbage was by far the most highly used anthropogenic food source. While garbage was consumed in high amounts every year, the poor years (years when less natural food sources were available) accounted for much higher levels of garbage consumption. The amount of garbage consumed during Hyperphagia was 5 greater during poor years.

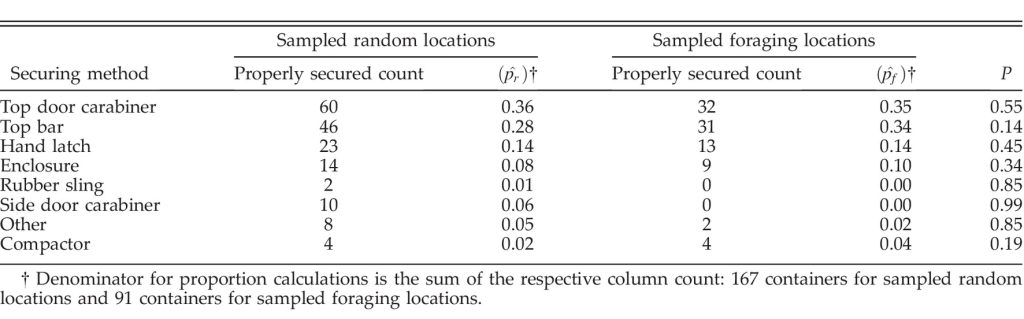

The researchers randomly sampled 384 garbage containers and found that 76% of them were bear-resistant, but only 57% of the bear-resistant containers were properly secured.

Discussion:

The researchers determined that Black bears are most driven by cost vs reward when foraging. They put in the least amount of effort for the highest amount of caloric intake. They determined that the best next action is to decrease the reward bears receive when foraging in garbage, or increase the amount of effort put in. That would hypothetically steer bears towards foraging in wild land areas more often.

Critiques and takeaways:

Overall, I found the methods of this study to be fairly reliable in reducing potential bias and effectively answering the research question. The researchers were able to analyze 2 good years and 2 bad years. They were able to follow a decent sample size of bears, and collect data from a high number of feeding locations. They did, however, not dive deep into the dynamics within the wild land areas surrounding Apen, Colorado. This makes sense since the purpose of this study was to find answers specific to urban Black bear foraging behavior. This does raise a couple of questions that could aid in the understanding of urban Black bear foraging behavior though. Mostly, I think it’s worth researching Black bear population dynamics in the surrounding wild areas. Are these urban bears only urban because they are being pushed out of natural spaces by more dominant bears? Is there a lack of food sources available to sustain the whole Black bear population in these areas? How does hunting or a lack thereof play into the need for bears to travel into urban areas? To what degree are Black bears bothered by entering urban areas, and how bad do the alternatives need to be to push them there?

Those are a lot of questions, but I think it would be very interesting to conduct research that could answer some of these questions in wild land locations surrounding Aspen, Colorado in order to best relate results to one another.

Article:

URL: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1890/ES15-00137.1

Citation: Lewis, D. L., S. Baruch-Mordo, K. R. Wilson, S. W. Breck, J. S. Mao, and J. Broderick. 2015. Foraging ecology of black bears in urban environments: guidance for human-bear conflict mitigation. Ecosphere 6(8):141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES15-00137.1