Overview

Human-Wildlife interactions are becoming increasingly common in urban areas. People are particularly concerned about interactions with carnivores, such as urban foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Urban foxes are often described as “bold” or “fearless,” but this study challenges that idea by breaking down what “boldness” actually means. In this study, the authors focus on two key behaviors: neophobia, which is the fear of new things, and wariness, which is the fear of potential threats. The authors then explored how these traits vary depending on a fox’s social status. They wanted to know whether dominance within a group, rather than city living itself, shapes how foxes behave around unfamiliar or risky situations.

Methods

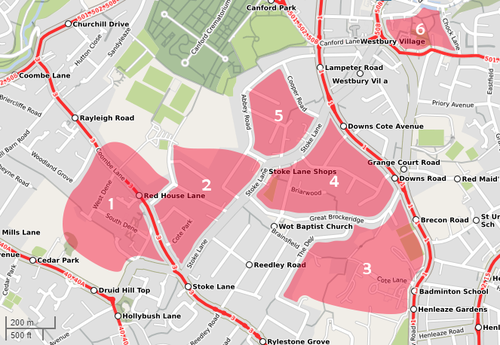

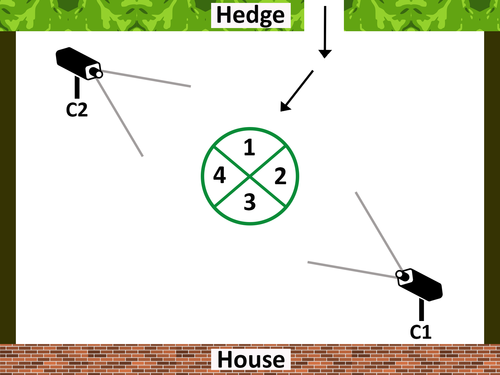

The study was conducted in northwest Bristol, England, an area with a well-documented history of urban fox research. Six fox social groups were observed across residential neighborhoods, each with its own territory. Within each territory, researchers worked with homeowners who already fed foxes, setting up small experimental arenas in their backyards. This approach increased visitation rates and allowed for consistent observations without drastically altering the foxes’ normal behavior.

Two main experiments were designed to measure different responses. The first was a novelty test, which measureed neophobia. During this test, a shiny reflective garden ornament was placed near a food source to represent an unfamiliar object. The second tested wariness, introducing a line soaked in wolf urine, a scent cue meant to simulate a natural predator. These experiments were conducted during two 20-day periods: one in late November and early December, and another in May, to test for possible seasonal effects. Food was placed in the arena each evening to attract foxes, and all activity was recorded using motion-sensitive cameras positioned to capture multiple angles.

Researchers identified individual foxes by their distinct markings, scars, and tail shapes, and ranked them as either dominant or subordinate based on observed interactions. Dominant foxes typically controlled territory use and access to food, while subordinates tended to be younger, lower-ranking individuals. The team recorded each fox’s hesitation time, level of alertness, time spent feeding, and frequency of entries into the test area. They then analyzed these behaviors using principal components analysis (PCA) and linear mixed models to look for patterns between social status, season, and social context (foraging alone or with others).

Results

The study found that dominant foxes were more cautious, showing higher levels of both neophobia and wariness. They approached new or threatening objects more slowly and displayed longer periods of vigilance. Subordinate foxes were more exploratory and willing to take risks, likely due to their lower access to food and greater need to forage widely. When foxes were observed with others, both dominants and subordinates were less fearful, suggesting that social presence reduces perceived risk. Season had no significant effect, meaning social structure was the strongest factor shaping behavior.

Discussion

These results suggest that the “bold” foxes people often see near homes or gardens are usually subordinates taking greater risks to survive, not animals evolving to be braver, which is important for wildlife management. Actions like culling, which remove dominant individuals, can break up social groups and lead to an increase in subordinate foxes.

Critical Analysis

I thought the authors of this paper did a good job linking fox behavior to social structure and challenging the idea that urban foxes are simply “getting bolder.” However, I feel like the novelty test could have been more controlled as the ornament used moved in the wind and reflected light, which likely triggered several reactions at once, making it hard to tell what actually caused the foxes’ hesitation. Another limitation is that all testing occurred in feeding backyards, where foxes were already comfortable around people. Including non-feeding sites would make results more representative of typical urban fox behavior.

Reference

Padovani, R., Shi, Z., & Harris, S. (2021). Are British urban foxes (Vulpes vulpes) “bold”? The importance of understanding human–wildlife interactions in urban areas. Ecology and Evolution, 11(2), 835–851. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7087