Habitat fragmentation and destruction is one of the primary drivers of extinction and species’ endangerment in today’s ever-evolving world. With impervious surfaces becoming very prevalent as urban areas continue to grow and sprawl, animals are left without safe passageways within urban settings. One solution that has gained traction and support are ecological corridors. Ecological corridors or wildlife corridors are physical green spaces that are protected from surrounding human development that allow for a natural passageway between dangerous environments such as highways, cities, and other development.

One study in France in 2020 wanted to test the efficacy of these corridors through various least-cost paths (LCPs) that both reduce cost of development of a corridor with success-rate of a well-used corridor by wildlife. This study was done primarily using mark-release-recapture (MRR) methods for moths, and using audio playback of calls for passerines to get a broader scope of data for determining future landscape planning decisions for wildlife corridors.

The study area for this research consisted of two medium-sized cities within France (Rennes and Lens). Both sites were comprised of a rough half and half split between “artificialized surfaces” (man-made structures, developments) and urban green spaces (parks, yards, large medians). The study groups of moths and passerines were carefully picked for both their vulnerability to urban development and their previously noted behaviors with movement across urban settings.

After determining the habitat data for each experimental group, the study modeled a few predictions for effective corridors using LCP models in ArcGIS. In these models, they cross-referenced high density habitats with rough resistance values of the animals to travel/move near specific land types.

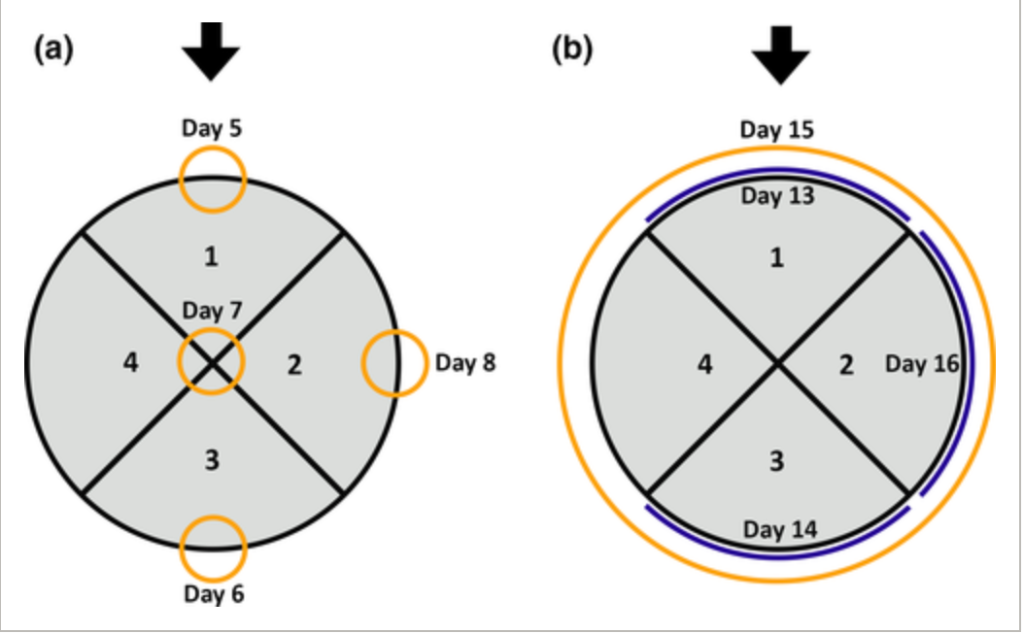

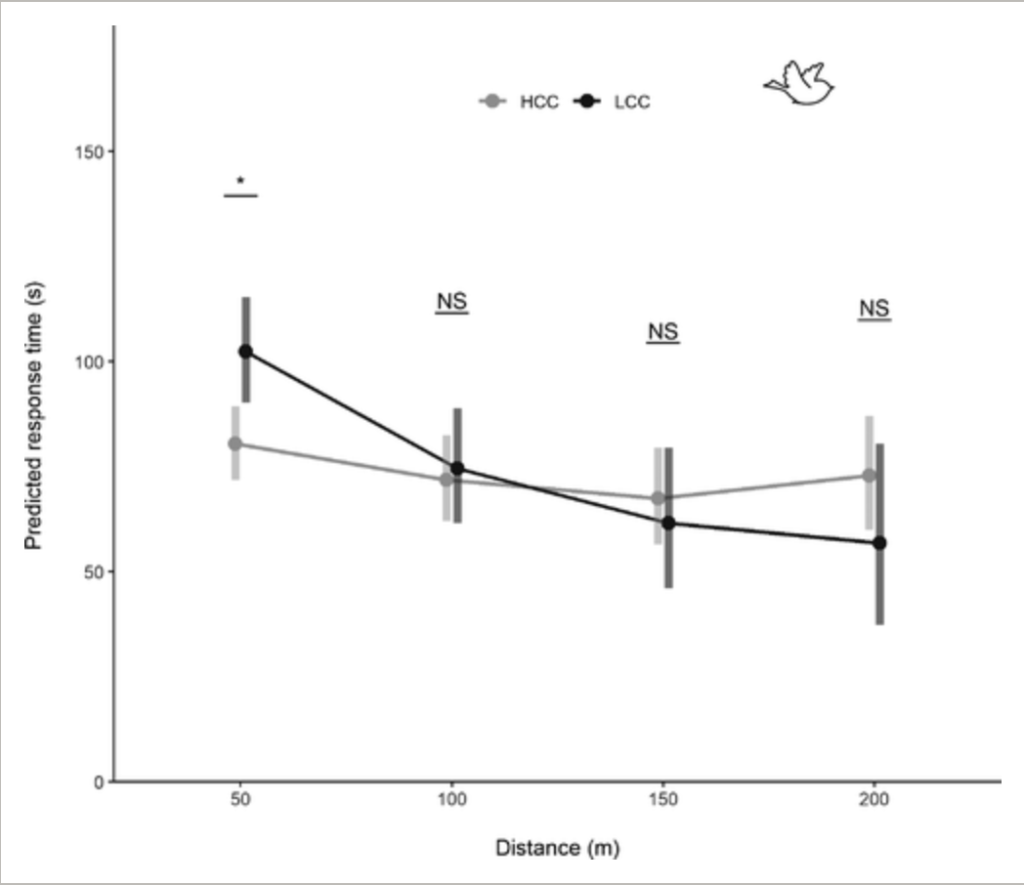

The mark-release-recapture for the moth study group was conducted in 2015 in Lens and 2016 in Rennes, with results primarily relying on the amount of individuals recaptured within specific areas across the city. Additionally, each recapture was replicated three times per area for accuracy.

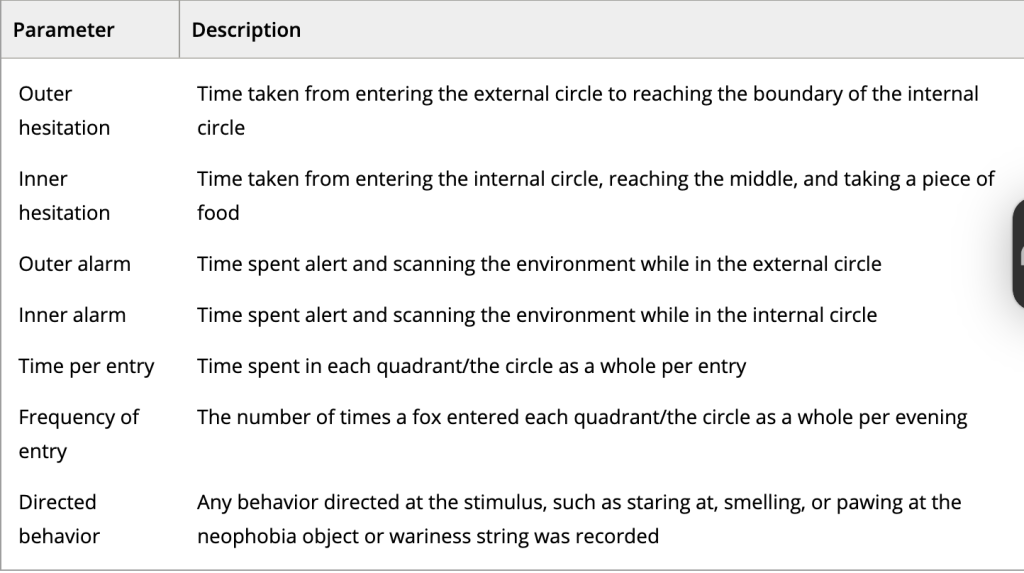

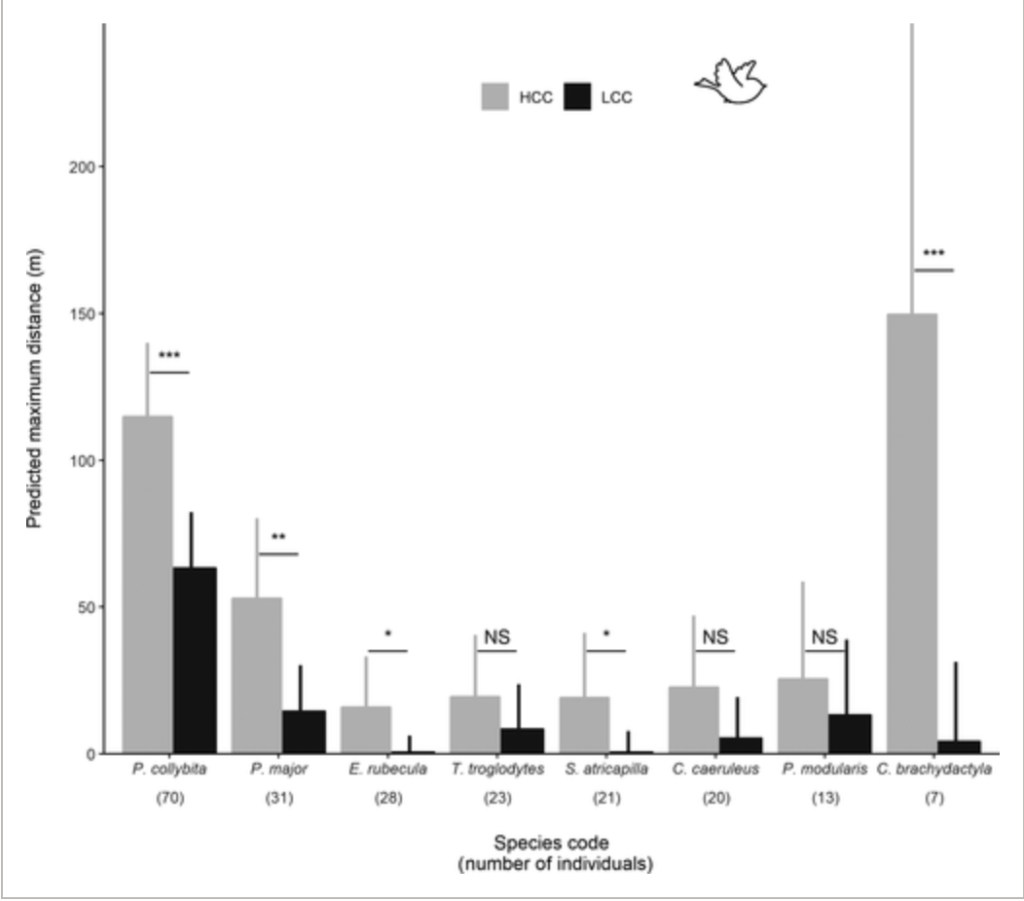

Then the playback recalls for the passerine study group were conducted from April to May in Lens and 2016 in Rennes. These trials were to test response behavior of passerines to specific areas based on development. The variables for this group were testing how far an individual would fly based on the artificial calls and their response time to the call.

The data was collected into mixed models to contextualize the connectivity in context with the variables tested of moths and birds to the different levels of urban development. The amount of connectivity was categorized into two different sections, highly connecting contexts (HCCs like green spaces and less developed areas) and less connecting contexts (LCCs like buildings, impervious surfaces, and more developed areas).

For the moth recapture group, among marked individuals, 77% of them were recaptured in HCC areas and and 23% were recaptured in LCC areas.

For the passerine callback group, 66% of birds had a positive response (significant movement speed and distance moved). Overall, in the HCC areas, it was observed that there was significantly higher movement distance (~84m) and speed on average than in LCC areas (~46m). Additionally, there was a longer delay in response from passerines within LCC areas than in HCC areas.

The larger results show that moths were 4 times more likely to be recaptured in HCC than in LCC areas. However, the study admits that some likely explanations for this could have been due to the presence of light pollution and habitat fragmentation within the cities when compared to natural habitats. This supported the original hypothesis that natural areas do help to facilitate moth movement and dispersal. Similarly, passerines did travel significantly more in HCC than LCC areas. Also, since passerines reacted quicker in HCC areas, it suggests that they do react quicker with territorial behaviors in more natural settings. This shows that urban matrixes could be contributing to an overall slowing down of both movement and responses from local wildlife.

For future research, the study suggests that shifting to more small mammals studies in a similar habitat connectivity context could be useful for aggregating data and drawing more connections for urban planners. Additionally, this study included many species from both moths and passerines, and still seeing large trends towards more movement and faster responses in natural settings, showing that this effect is not specialized towards specific species. However they also point out that every single city is going to have a slightly different matrix of developed to non-developed areas, hampering the ability for a blanket-approach to be possible. In future studies and urban planning, specialized research and approaches need to be taken in context to the city they are taking place in. Only broader knowledge of impacted behaviors and movements can be applied across multiple areas for baseline understanding to be built upon.

Balbi, M., Croci, S., Petit, E., Butet, A., Georges, R., Madec, L., Caudal, J. & Ernoult, A., (2020, November 24). Least-cost path analysis for urban greenways planning: A test with moths and birds across two habitats and two cities. Journal of Applied Ecology, Volume 58, Issue 3, Pages 632-643, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13800