Invasive Species in Penguin Worlds:

An Ethical Taxonomy of Killing for Conservation

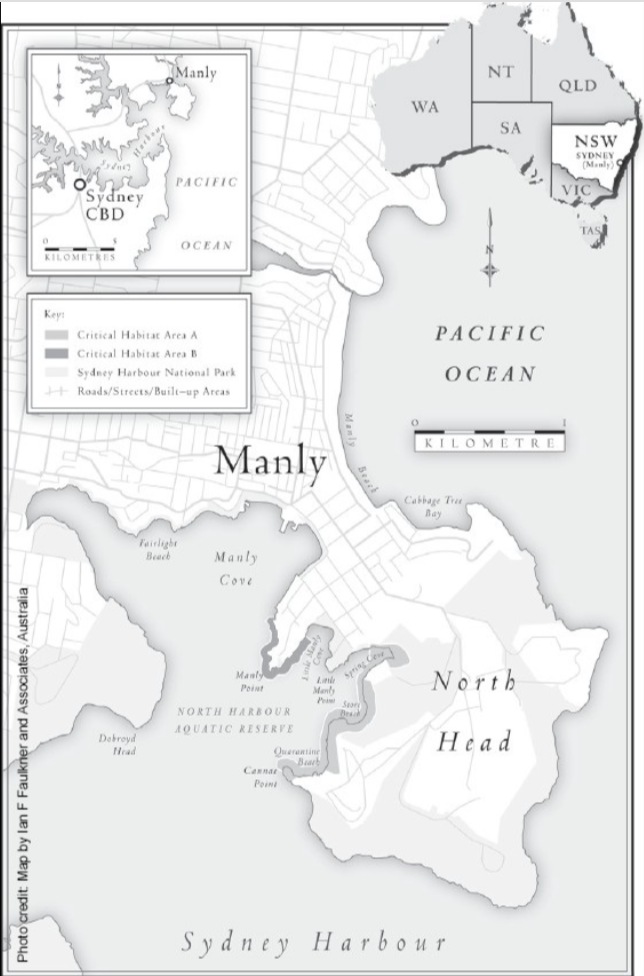

Within this study, Van Dooren (2011) evaluates numerous different conservation strategies used on an endangered population of small penguins (Eudyptula minor) living in Sydney’s North Harbour, to explore which types of intervention, both human and non-human, are acceptable, and assess the ways in which we justify these interventions. Van Dooren (2011) explores many of the reasons that the term “invasive” has been deemed so problematic. Specifically, this article focuses on investigating much of the conservation legislation and practice within New South Wales, and the somewhat unusual methods that are employed to classify these various organisms. This article highlights the need to reconsider current invasive species management strategies, as opposed to being innately attracted to the “easiest” solution, instead prompting open and inclusive conversations about the goals, values, and priorities of all parties involved to create more multifaceted management solutions.

Van Dooren (2011) explores various attempts to manage predation threats to an endangered population of little penguins (Eudyptula minor) living in Sydney’s North Harbour. Van Dooren (2011) begins by introducing the first threat to the small penguins, in the form of the exotic red fox (Vulpes vulpes). The solution offered for this species of concern was total eradication through baited poison traps. This practice was conducted widely, not only within the Sydney Harbour National Park, a known area of habitat for the small penguins, but also throughout many local councils as they engage in intensive red fox control. While consuming the poison does eventually result in death, it first causes the foxes to engage in ‘manic running, yelping, shrieking, and then collapse and convulsions’, all of which usually lasts several hours” (Van Dooren, 2011). This very controversial, lethal control method was allowed to continue largely as a result of the simplistic divide that exists between native and exotic species within conservation legislation in New South Wales. This mass slaughtering continued even after biologists had raised significant ecological concerns with the eradication of the foxes, as removal had been known to lead to increased mortality among some native birds and animals throughout the area. Additionally, without the foxes, rabbit populations have on occasion exploded, resulting in additional problems for valued native herbivores and plant species.

Van Dooren (2011) goes on to discuss a considerable native threat to the little penguin population, the New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsteri). When proposing solutions for this issue, the fur seals were approached very differently than the foxes, largely in that they are presented as ‘native’ to the area, and therefore engaged in ‘natural predation’ of this colony. It is also highlighted that it is important to recognize that fur seals differ from foxes in that not every fur seal will eat the little penguin species, as a species. These seals are certainly not small penguin specialists; however, there are documented examples of New Zealand fur seal populations that relied quite significantly on them for a large part of their diet. The solution introduced to deal with this threat to the little penguin colony was essentially to ignore this issue. There was no mention of this native fur seal species in the protection and restoration plans for the small penguin population, indicating that since they are native to the ecosystem as the species of concern, there is no need to prevent their killing of the already shrinking population, an obvious double standard.

This article juggles with the problematic idea of coining the species’ “invasiveness” as it applies to the various predators of these small penguins. Van Dooren (2011) also uses these case studies to explore the influence of these rhetorical distinctions in determining species as threats, not only in the context of the continuity of this penguin colony, but also in a broader ecological sense. Additionally, Van Dooren (2011) mentions that in certain cases, native species have been referred to as “invasive pests,” largely when they induce prolonged substantial damage to other native species. Van Dooren (2011) argues that along with these “invasive” natives frequently comes a recent history of human actions altering their population or distribution, resulting in their destructive title. So we ask, in the absence of the convenient simplification of harmful being synonymous with invasive, how do we determine appropriate regulatory actions to take against these species, or if we should act at all? What kinds of interventions, either from humans or nonhumans, are warranted, and which are deemed too extreme? Van Dooren (2011) argues that by placing a binary divide between native and exotic species, experts fail to acknowledge the dynamic and ever-changing nature of the ecological systems these species exist in. These divides frequently act as a justification for which species should be protected or destroyed, as their values are intrinsically tied to the terminology

One critique that I have of this article is just how heavily it leans into critique. While Van Dooren (2011) does a great job at pointing out several of the extremely problematic aspects of designing and enacting invasive species management plans, both on an ecological and ethical level, he falls flat in describing any specific actionable solutions for these issues. Furthermore, Van Dooren (2011) creates his narrative through very rose colored glasses, leaning very heavily into the idea that killing should be a last resort. While I do not necessarily disagree with the fact that killing should be taken very seriously, and every other option should first be examined, it is willfully ignorant to state that there is never a case where it is the most practical solution. Finally, on an accessibility level, this article is written in a form that relies very heavily on jargon. This article discusses various aspects of invasive species management that must take place in highly human-dominated, urban, and suburban areas. As a result, Van Dooren (2011) has structured this article in a way that is more palatable to the general public; however, he did not translate that same consideration to the vocabulary of the article. This article could definitely be improved upon by relying less on jargon and making the language more accessible to a multitude of audiences.

Source:

Van Dooren, T. (2011). Invasive species in penguin worlds: An ethical taxonomy of killing for

conservation. Conservation and Society, 9(4), 286. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.92140