Overview:

The title of the article I will be reviewing is “Greater consumption of protein-poor anthropogenic food by urban relative to rural coyotes increases diet breadth and potential for human–wildlife conflict”. This study focuses on the diet of an urban-adapted generalist species called Canis latrans, more commonly known as coyotes. This species has been increasingly present in urban environments, and this has led to dietary changes for urban coyotes. This study examines how these urban coyotes have adapted to consuming more anthropogenic food sources in their diet (bird seed, compost, pet food, trash, etc.). Although having a broad number of dietary sources can benefit coyotes, consuming these anthropogenic sources may lead to increased amounts of human-wildlife conflict in urban areas. Coyotes are very flexible when it comes to their dietary and environmental needs, so this explains why urban coyote populations have been increasing in recent years. In order to better understand the role of anthropogenic food sources in urban coyote diets and how these impact human-wildlife conflicts, this study compared the diets of urban and rural coyotes. It aimed to determine what kinds/amounts of anthropogenic food were part of urban coyote diets and how this impacted the prevalence of conflicts between urban coyotes and humans.

Methods:

The diets of coyotes from several urban and rural areas of Canada were compared for this study. The researchers collected samples of coyote scat and hair to conduct the necessary analysis for this experiment. The scat samples were collected in a variety of areas that had either received reports of coyote sightings, had coyote tracks, or where radio-collared coyotes had been located. Several characteristics were utilized to distinguish the coyote scat from other similar species such as domestic dogs, wolves, or foxes. The items found in the scat were categorized to separate natural and anthropogenic food sources. The prevalence and relative abundance of each diet component were calculated for both the urban and rural coyotes. These comparisons were able to give an in-depth understanding of the differences between urban and rural coyote diets.

The hair samples were collected for the purpose of performing stable isotope analysis. These samples were taken from coyotes that had known histories of having conflicts with people. This type of analysis was able to give an accurate and longer-term view of anthropogenic food consumption by the coyotes of interest. The hair samples were taken from coyotes that had been live-trapped as well as ones that had been killed for various reasons. In order for a coyote to be categorized as conflict-prone, it had to have received complaints from the public regarding its behavior. The bodily conditions of each coyote were observed at the time that the hair sample was retrieved, and each coyote was analyzed for disease (sarcoptic mange infestation). Once the hair samples were obtained, they were used to perform the stable isotope analysis.

Results:

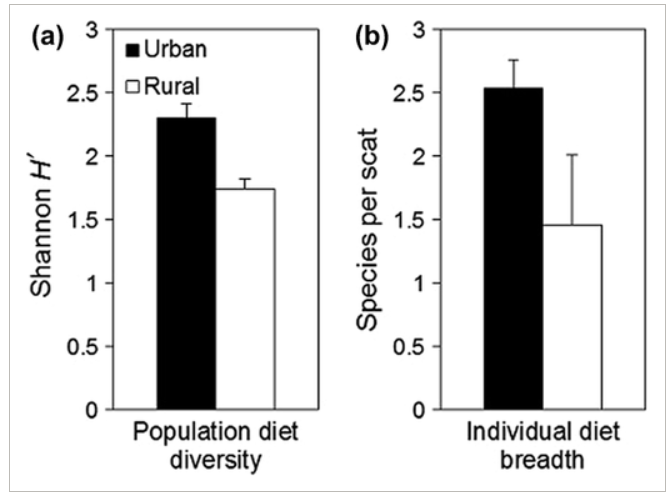

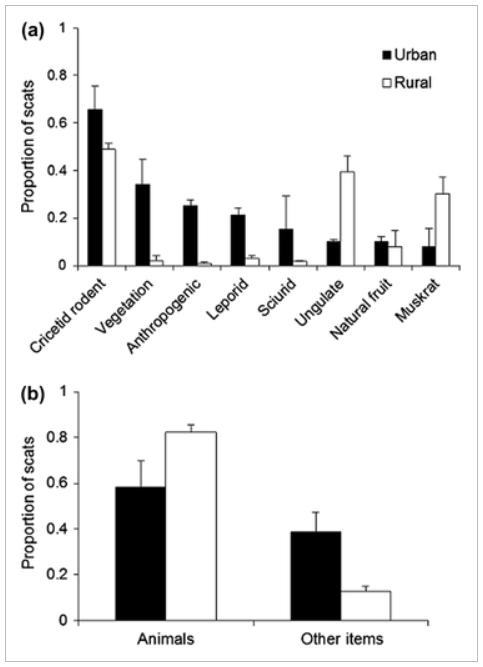

The analysis of scat samples found that urban coyotes had more diverse diets when compared to rural coyotes. This was true at both the population level and the individual level. It also showed that urban coyotes consumed anthropogenic food sources much more often than rural coyotes (26% of all urban coyote scat samples and <1% of all rural coyote scat samples). Additionally, urban coyotes consumed far less animals when compared to rural coyotes. However, urban coyotes did consume small mammals more frequently than rural coyotes.

Figure 2 Diet diversity of urban coyote scats from two urban (black bars) and two rural sites (white bars). We measured population diet diversity by calculating Shannon’s H′ index from pooled scats (a) and measured individual diet breadth using the number of species per scat (b). Bars show mean values and error bars indicate standard error.

Figure 3 Differences in prey use in urban (black bars) and rural (white bars) coyote scats from two urban and two rural studies in Alberta, Canada. (a) The frequency of occurrence (displayed as proportion of scats that contained item) for the diet items that differed significantly between urban and rural coyotes. (b) The proportion of analyzed scats from urban or rural coyotes that contained prey remains such as hair, bones, or teeth (animals) and all other items including anthropogenic food. Error bars show standard deviation.

The analysis of the hair samples was able to support several conclusions. Urban coyotes were more likely to experience poor bodily conditions and disease presence. This was also true for urban coyotes that had behaved in conflict-prone ways. The coyotes that had not caused human-wildlife conflict were less likely to have poor bodily conditions and disease. The urban coyotes did consume more anthropogenic food, but they did consume similar amounts of protein as rural coyotes. Interestingly, this study found that the conflict-prone urban coyotes did not consume significantly more anthropogenic food sources. However, it did find that the conflict-prone urban coyotes did consume significantly less protein when compared to all other sampled coyotes.

Reflection/Critiques:

Overall, this study was able to confirm that urban coyotes had more diverse diets when compared to rural coyotes. This is largely due to the consumption of additional anthropogenic food sources by urban coyotes. Additionally, conflict-prone urban coyotes consumed similar amounts of anthropogenic food sources. However, these coyotes consumed less protein when compared to the rest of the samples.

The use of anthropogenic food sources has likely contributed to the increased prevalence of coyotes in urban areas. These additional food sources allow coyotes to be less reliant on any one particular source of food, which increases their likelihood for survival. Anthropogenic food sources are often consistently available, which may cause coyotes to favor them over natural food sources in some scenarios.

This study aimed to determine if the use of anthropogenic food sources increased the prevalence of human-coyote conflicts in urban areas. According to its findings, the consumption of anthropogenic food sources does not drive these conflicts. Instead, the amount of protein consumption by coyotes was correlated with the likelihood of them exhibiting conflict-prone behavior. The coyotes that were reported as being conflict-prone had significantly less protein in their diets and were more likely to be in poor health. These coyotes likely exhibited conflict-prone behaviors due to their lack of health and bodily vigor. They would likely be more reliant on anthropogenic food sources since they can be easily obtained and are consistently available.

One critique for this paper is that the scat samples were collected across multiple different years in each location. This is problematic because many influential variables can change over these long time periods. Things such as weather, prey populations, predator populations, human presence, urbanization, and anthropogenic food sources can change significantly across multiple years. This decreases the reliability of the conclusions that were drawn from the analysis of the scat samples. Although it is not completely clear how much this would impact the findings, it certainly has some meaningful impact and should be acknowledged.

Another critique is that there was a small and unevenly distributed sample size for the coyote hair analysis. According to the paper, only 72 hair samples were analyzed across urban and rural coyotes. Of these samples, 49 were urban and 23 were rural. This is problematic because the overall sample size is small, which decreases the statistical soundness of any conclusions that were drawn from it. Additionally, far more urban samples were analyzed when compared with rural samples. This increases the likelihood of random variation causing inaccurate results for the rural samples since there were so few. This issue could be fixed by increasing the total number of samples and by ensuring that they were evenly distributed between urban and rural coyotes.

Reference:

Murray, M., Cembrowski, A., Latham, A.D.M., Lukasik, V.M., Pruss, S. and St Clair, C.C. (2015), Greater consumption of protein-poor anthropogenic food by urban relative to rural coyotes increases diet breadth and potential for human–wildlife conflict. Ecography, 38: 1235-1242. https://doi-org.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/10.1111/ecog.01128